I read the signs, I got all my stars aligned

My amulets, my charms, I set all my false alarms

So I'll be someone who won't be forgotten

I've got a question and you've got the answer

I've been working on a real, serious blog post about gender, language, and science fiction for about 3 months now. It will finally be ready before the end of next month. Here's something entirely different to read while you wait for that post, which, when it finally gets here, is going to be pretty rad.

~ ~ ~

I've been using Goodreads for four or five years now. Like most social media, I waver between thinking of it as a bad habit or a useful tool. Unlike other social media, though, Goodreads is really not about creating, curating, and presenting a public persona. Instead, Goodreads is more of a endlessly drawn out contest with myself that I can never win.

Goodreads makes the organic, natural, amorphous process of reading books into a concrete numbers game. Before I met Goodreads, I never counted how many books I read in a year, I didn't think about how many pages I read, and when I stopped reading a book in the middle somewhere and set it aside, I eventually just forgot about it. Now I compare every year's books read to past years (this year: 44; last year: a whopping 87—I had a lot of free time in 2014, tell you what) as well as the years' respective page counts. I've also been reminded continually for the last 6 months that I started two books and did not finish them, a fact which I am have been trying to bring myself to resolve one way or the other for what seems like forever.

Goodreads encourages you to assign a score to the books you read, as if they could all be boiled down easily to a single dimension: good or bad, yes or no, liked it or didn't. And I do this with every book I read, even though it's absurd. What follows are short descriptions of all the books I rated 5 out of 5 stars this year (their order is the order I read them in). They're wildly different—varying considerably in scope, quality, genre, depth, length, and in dozens of other ways—but Goodreads does not ask me about these things, and I would probably be even more unhappy if it did.

~ ~ ~

The Book: The Resurrection of the Son of God, by NT Wright

What It Is: A pretty dense and thorough investigation of the Resurrection of Jesus.

Why I Read It: I finished the first two books in NT Wright's series of really huge and important books about the New Testament and history and theology and whatnot and decided to keep going. I subsequently crashed and burned when it came to finishing the next book, the 1700-page behemoth Paul and the Faithfulness of God.

You Should Read It If: You are a hardcore Bible nerd and/or want someone to tell you in hella detail what's up with the Resurrection.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It's an excellent book, a serious scholarly achievement, and I was proud of myself for finishing it.

Why I Read It: I read and loved David Mitchell's 2014 novel The Bone Clocks and wanted to read the book that made him a star.

You Should Read It If: You somehow made it out of the last ten years without someone making you read it and also you didn't watch the movie.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: I wouldn't say it changed my life, but the book is like nothing else I've read, in a really good way.

The Book: Class Action, by Shawn Gude and Bhaskar Sunkara (eds.)

What It Is: A series of essays critiquing current trends in education and advocating better educational systems and methods from a left-wing political viewpoint.

Why I Read It: I am an aspiring educator and leftist.

You Should Read It If: You are a leftist, or a teacher, or both, or if the creeping privatization of our nation's education worries you.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: I haven't thought about it too much since, having already internalized most of its basic ideas, but I felt at the time that it was a really important book that other people should read. Maybe I wanted to help bump up its score on Goodreads—it doesn't have many reviews.

The Book: Debt: the First 5000 Years, by David Graeber

What It Is: A really, really broad history of money and debt; the author, an anarchist activist and anthropologist, attempts to track the subject across literally the whole of human history.

Why I Read It: I read about it on the science fiction website Tor, where it was recommended as a way of getting into the mindset required to create alien societies. This was, it must be said, a pretty weird way to stumble across this book.

You Should Read It If: You want to have a good time learning about the history of money and aren't too hung up on whether every detail of what you read is true.

The Book: Class Action, by Shawn Gude and Bhaskar Sunkara (eds.)

What It Is: A series of essays critiquing current trends in education and advocating better educational systems and methods from a left-wing political viewpoint.

Why I Read It: I am an aspiring educator and leftist.

You Should Read It If: You are a leftist, or a teacher, or both, or if the creeping privatization of our nation's education worries you.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: I haven't thought about it too much since, having already internalized most of its basic ideas, but I felt at the time that it was a really important book that other people should read. Maybe I wanted to help bump up its score on Goodreads—it doesn't have many reviews.

The Book: Debt: the First 5000 Years, by David Graeber

What It Is: A really, really broad history of money and debt; the author, an anarchist activist and anthropologist, attempts to track the subject across literally the whole of human history.

Why I Read It: I read about it on the science fiction website Tor, where it was recommended as a way of getting into the mindset required to create alien societies. This was, it must be said, a pretty weird way to stumble across this book.

You Should Read It If: You want to have a good time learning about the history of money and aren't too hung up on whether every detail of what you read is true.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It radically changed my understanding of money and several other facets of human history. In retrospect, I should have been discerning enough to realize that the book is somewhat beyond the scope of the author's expertise; as it is, some of the historical and factual claims he makes are clearly wrong. I still think it's a good book, but I want to do some more fact checking before I recommend it to others.

The Book: Saga Deluxe Edition, Volume 1, by Brian K. Vaughan

What It Is: A fantasy space opera about war and family and sex and death. Star Wars for grownups.

Why I Read It: I wanted to give a signed copy of it to my friend Daniel for his birthday and I needed to make sure the actual, physical book I bought him was in good shape to get signed. I also love the books.

You Should Read It If: You are an adult who likes Star Wars but also knows that it is for children.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It contains a lot of Saga, which I love, as well as commentary on the creation of Saga by author Brian K. Vaughan, who I also love.*

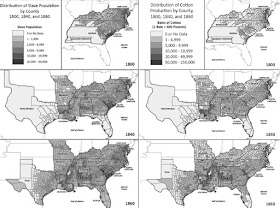

The Book: The Half Has Never Been Told, by Edward E. Baptist

What It Is: An in-depth history of U.S. slavery, which makes a strong case for slavery as the economic engine driving the U.S. economy in the first half of the 19th century.

Why I Read It: I had to pick a book for a history class book report and decided to be an overachiever about it. I actually posted the review here on this blog earlier this year.

You Should Read It If: You want a lot of information about American slavery, compellingly presented.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It presents very detailed and potentially dull research in a lively, personable way. The subject is one I care a lot about.

The Book: The Inverted World, by Christopher Priest

What It Is: A piece of a sort of anti-science-fiction, in which the main character turns out not to be the hero of the story (nor the villain), and who cannot accept that the strange world he gradually learns about and masters is actually a distortion and a lie.

Why I Read It: I love this book and hadn't read it in a few years.

You Should Read It If: You like good books about weird and vaguely unsettling (but not creepy or gross) things.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: This is one of my all-time favorites, a book I try to read every few years. It's strange and lovely and slightly upsetting all at once.

The Book: The Martian, by Andy Weir

What It Is: A software engineer's idea of a good book, combining humor, adventure, and a constant stream of life-threatening technical problems with hastily assembled solutions.

Why I Read It: I wanted to read the book before I saw Matt Damon in the movie.

You Should Read It If: You missed the movie. Or: You saw the movie and want slightly more jokes and a lot more descriptions of engineering puzzles.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: While it's not a great work of literature, it was a really genuine pleasure to read--lots of fun, quick, light, and exciting.

The Book: Alif the Unseen, by G. Willow Wilson

What It Is: Modern fantasy set in an unnamed mideast police state during the Arab Spring.

Why I Read It: It had been on my list for ages, who knows where I heard about it from, and I finally just caved and tracked down a copy.

You Should Read It If: You read the Arabian Nights and thought, Yes, this, but with computers also.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It's lighthearted and fun. I haven't really thought much about it since, but I liked it a great deal at the time.

The Book: The Fifth Season, by NK Jemisin

What It Is: High fantasy, concerning a world constantly beset by earthquakes, in which the powers that be maintain control through a caste of enslaved wizards with the power to create and prevent tectonic events.

Why I Read It: I am obsessed with NK Jemisin's work and read everything of hers I can get my hands on. Her work is unusual in that it is speculative fiction that acknowledges that people of color exist. It shares this quality with some of my other favorite authors of late: Octavia E. Butler, Nnedi Okorafor, and Samuel R. Delany.

You Should Read It If: You are a literate human being.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It's a great book, but also I really just want NK Jemisin to win.

The Book: The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. Le Guin

What It Is: A classic work of science fiction about a planet where gender doesn't exist and everyone is both sexes at once.

Why I Read It: For the big project I'm working on that I mentioned at the top of this post.

You Should Read It If: You are a reader of speculative fiction who has somehow not already read this stone cold classic of the genre.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: It's a gorgeous book that I loved reading and wished I had more of when I was done.

The Book: Saga, Volume 5, by Brian K. Vaughan

What It Is: Saga, only more so.

Why I Read It: I love Saga in particular and Brian K. Vaughan's work in general.

You Should Read It If: You read Saga Deluxe Edition, Volume 1 or any other edition of Saga issues 1 through 18.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: I'm honestly not sure. In terms of innovation, enjoyability, and other qualities, it's probably a little behind the first two volumes. But what the hey: I love them all equally and unconditionally.

The Book: Saga, Volume 5, by Brian K. Vaughan

What It Is: Saga, only more so.

Why I Read It: I love Saga in particular and Brian K. Vaughan's work in general.

You Should Read It If: You read Saga Deluxe Edition, Volume 1 or any other edition of Saga issues 1 through 18.

Why I Gave It 5 Stars: I'm honestly not sure. In terms of innovation, enjoyability, and other qualities, it's probably a little behind the first two volumes. But what the hey: I love them all equally and unconditionally.

~ ~ ~

Why use Goodreads at all? The list above does not reflect which books I thought about the most, or which most changed my view of the world, or which I most want to recommend to friends. (I think about We Who Are About To, Ancillary Justice, and Galileo's Middle Finger much more often than, say, Alif the Unseen or The Martian, in spite of having rated them lower.) Assigning a rating is clearly arbitrary, often based on momentary whims. I never rate a book one star, because that would involve forcing myself to read all the way through a book that I hate (or to rate a book I had not finished), so a big part of the rating system is wasted on me.

So it's clearly not for the rating system that I use this service. One big use I get from it is the ability to track books I want to read in the future, without declaring that I necessarily want to own them by, say, putting them on an online wishlist. Even that, though, can turn into a burden--my To Read list is too long to expect to ever actually finish; I will end up forgetting why I was interested in many of its books long before I get around to reading them, and in the meantime, I will feel guilty about not reading them.

Here's the real reason I keep going: Goodreads feels like posterity. It's a reminder that I've accomplished things I set out to do with purpose. It's like a little record of what I was thinking about over the years; long since I've forgotten the day-to-day events, I can look back and see that I was interested in, the speculative fiction of Jeff VanderMeer in the second half of 2014, the historical Jesus in fall 2013, and the Master and Commander novels throughout 2012. That's a good feeling, and for that alone, if for nothing else, I plan to keep on keeping track of what I read, and what I think about it, using the magic of the internet.

*Here is a picture of the two of us:

So it's clearly not for the rating system that I use this service. One big use I get from it is the ability to track books I want to read in the future, without declaring that I necessarily want to own them by, say, putting them on an online wishlist. Even that, though, can turn into a burden--my To Read list is too long to expect to ever actually finish; I will end up forgetting why I was interested in many of its books long before I get around to reading them, and in the meantime, I will feel guilty about not reading them.

Here's the real reason I keep going: Goodreads feels like posterity. It's a reminder that I've accomplished things I set out to do with purpose. It's like a little record of what I was thinking about over the years; long since I've forgotten the day-to-day events, I can look back and see that I was interested in, the speculative fiction of Jeff VanderMeer in the second half of 2014, the historical Jesus in fall 2013, and the Master and Commander novels throughout 2012. That's a good feeling, and for that alone, if for nothing else, I plan to keep on keeping track of what I read, and what I think about it, using the magic of the internet.

*Here is a picture of the two of us: